| Bill McCoy's Natchez Trial |

To a novice starting down the river in a keelboat, this advice was given: "Keep the boat as much as

possible in the swiftest part of the current; never venture upon apparent cut-offs, unless the current is

strongest in that direction; whenever wishing to tie up at night, never do so alongside a falling bank, or near

tall timber, lest the bank should cave in as it does frequently on the Mississippi River, and the falling trees

crush the boat; watch for snags and sawyers, and once past these, beware of gangs of river thieves. Don't

pass their well-known lairs alone. Wait a few miles above, until you find other boats passing, and go on with

them......."

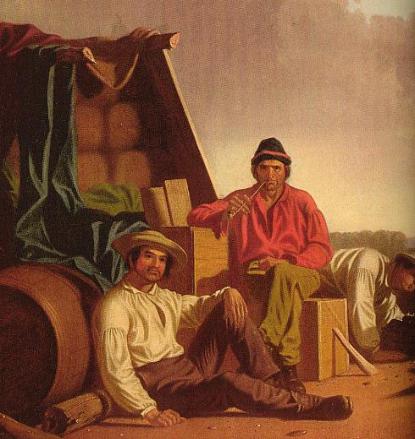

A race of gigantic, supermen, the keelboat developed. They thrived on overcoming obstacles. Snags

and sawyers, floating trees, shoals, bars, other boats, they took them in prideful stride. Many a

keelbaotman boasted that "his boat never swung in the swift current, and never backed from a "shute."

They were famous for feats of incredible strength, and for fights that would shame a Turk. "Rough frolics"

were their chief amusement, and likde a pressing hunger, their thirst for the fray had to be appeased

whenever the men made camp at night, or encountered other crews at such popular meeting places as

Natchez-Under-the-Hill.An early traveler on the river jotted down this boast which he over heard,

presumably at a distance, from a keelboatman: "I'm from the Lightning Forks of Roaring River. I'm all man,

save what is wildcat and extrs lightning. I'm as hard to run against as a cypress snag, I never back

water.......Cock-a-doodle-do! I did hold down a bufferlo bull, and t'ar his scalp with my teeth.....I'm the man

that single-handed towed the braodhorn (flatboat) over a sandbar, the identical infant who girdled a hickory

by smiling at the bark, and if any one denies it, let him make his will.......I can out-swim, out-sw'ar, out-jump,

out-drink and keep soberer, than any man at Catfish Bend. I'm painfully feroshus, I'm spiling for someone

to whip me, if there's a creeter in this diggin' that wants to be disappointed in tryin' to do it, let him yell,

whoop-hurra!"

It is of record that the peaceable inhabitants of the Natchez bluff looked down with horror upon the wild

bands of powerful "rowdies" who occasionally broke through the accepted boundaries of their own district

"under the hill" and carried the beautiful city by storm.

But withal, these physically perfect specimens had their own code of honor which included the unique rule

of proving friendship which perhaps cost Mike Fink his life.

For years, old-timers recalled the story of Bill McCoy. Bill was a veteran of every scrap on almost every

sand bar visible at low water on the Mississippi. He was, they said, the champion. After one particularly

vicious row, "where blood had been spilled and a dark crime committed," Bill was involved, and

"momentarily off his guard" he fell into the clutches of the law.

Brought before a court sitting at Natchez, Bill became the victim of mass hysteria, the demand to make him

the example and to punish him for the "oft-insulted majesty of justice." This happened just before the court

was to conclude its spring session.

Bill was charged, committed under $10,000 bail. At the last moment, a wealthy Natchez planter whom we

shall call Col. Williams came to his rescue and agreed to go his bail. McCoy went free.

Months passed. When the morning of the trial came, McCoy failed to appear. As the evening wore on,

everybody but Col. Williams was resigned to the inevitable.

The court was on the point of adjourning, when a cry went up in the street. A few moments later, a

strange figure stumbled into the courtroom. McCoy, his beard long and matted, his hands torn to pieces,

his eyes haggard, and sun-burned to a degree "that was painful to behold," fell prostrate on the floor from

sheer exhaustion.

Starting from Louisville as a "hand on a boat," McCoy found that, owing to the river's low stage and other

delays, it would be impossible for him to reach Natchez that way on time.

So he abanded the "flat," and with his hands, shaped a canoe out of a fallen tree. He had rowed and

paddled, almost without stop, hundreds of miles, to live up to his promise.

The trial was a formality, and Bill McCoy went free.

possible in the swiftest part of the current; never venture upon apparent cut-offs, unless the current is

strongest in that direction; whenever wishing to tie up at night, never do so alongside a falling bank, or near

tall timber, lest the bank should cave in as it does frequently on the Mississippi River, and the falling trees

crush the boat; watch for snags and sawyers, and once past these, beware of gangs of river thieves. Don't

pass their well-known lairs alone. Wait a few miles above, until you find other boats passing, and go on with

them......."

A race of gigantic, supermen, the keelboat developed. They thrived on overcoming obstacles. Snags

and sawyers, floating trees, shoals, bars, other boats, they took them in prideful stride. Many a

keelbaotman boasted that "his boat never swung in the swift current, and never backed from a "shute."

They were famous for feats of incredible strength, and for fights that would shame a Turk. "Rough frolics"

were their chief amusement, and likde a pressing hunger, their thirst for the fray had to be appeased

whenever the men made camp at night, or encountered other crews at such popular meeting places as

Natchez-Under-the-Hill.An early traveler on the river jotted down this boast which he over heard,

presumably at a distance, from a keelboatman: "I'm from the Lightning Forks of Roaring River. I'm all man,

save what is wildcat and extrs lightning. I'm as hard to run against as a cypress snag, I never back

water.......Cock-a-doodle-do! I did hold down a bufferlo bull, and t'ar his scalp with my teeth.....I'm the man

that single-handed towed the braodhorn (flatboat) over a sandbar, the identical infant who girdled a hickory

by smiling at the bark, and if any one denies it, let him make his will.......I can out-swim, out-sw'ar, out-jump,

out-drink and keep soberer, than any man at Catfish Bend. I'm painfully feroshus, I'm spiling for someone

to whip me, if there's a creeter in this diggin' that wants to be disappointed in tryin' to do it, let him yell,

whoop-hurra!"

It is of record that the peaceable inhabitants of the Natchez bluff looked down with horror upon the wild

bands of powerful "rowdies" who occasionally broke through the accepted boundaries of their own district

"under the hill" and carried the beautiful city by storm.

But withal, these physically perfect specimens had their own code of honor which included the unique rule

of proving friendship which perhaps cost Mike Fink his life.

For years, old-timers recalled the story of Bill McCoy. Bill was a veteran of every scrap on almost every

sand bar visible at low water on the Mississippi. He was, they said, the champion. After one particularly

vicious row, "where blood had been spilled and a dark crime committed," Bill was involved, and

"momentarily off his guard" he fell into the clutches of the law.

Brought before a court sitting at Natchez, Bill became the victim of mass hysteria, the demand to make him

the example and to punish him for the "oft-insulted majesty of justice." This happened just before the court

was to conclude its spring session.

Bill was charged, committed under $10,000 bail. At the last moment, a wealthy Natchez planter whom we

shall call Col. Williams came to his rescue and agreed to go his bail. McCoy went free.

Months passed. When the morning of the trial came, McCoy failed to appear. As the evening wore on,

everybody but Col. Williams was resigned to the inevitable.

The court was on the point of adjourning, when a cry went up in the street. A few moments later, a

strange figure stumbled into the courtroom. McCoy, his beard long and matted, his hands torn to pieces,

his eyes haggard, and sun-burned to a degree "that was painful to behold," fell prostrate on the floor from

sheer exhaustion.

Starting from Louisville as a "hand on a boat," McCoy found that, owing to the river's low stage and other

delays, it would be impossible for him to reach Natchez that way on time.

So he abanded the "flat," and with his hands, shaped a canoe out of a fallen tree. He had rowed and

paddled, almost without stop, hundreds of miles, to live up to his promise.

The trial was a formality, and Bill McCoy went free.

From Tales of the Mississippi; Samuel, Huber, Ogden; 1955.