Captain B. J. Reid, Company F, Sixty-third Regiment PA Volunteers

We are indebted to Alice Gayley for sharing the letter below with us.

To visit the excellent website, "Pennsylvania in the Civil War," which she hosts:

Click Here

We are indebted to Alice Gayley for sharing the letter below with us.

To visit the excellent website, "Pennsylvania in the Civil War," which she hosts:

Click Here

Bivouac at Fair Oaks, VA

Six and a half miles from Richmond

June 10, 1862

On the memorable 21st of May, our camp was about a mile this side of the Chickahominy, erecting a bridge. Colonel Hays and

Captain Berringer (acting Major) were three or four miles off, southward, inspecting the picket lines of our (Kearney's)

division. At 2 o'clock Company F went to a knoll across the railroad to bury Corporal Dunmire, who had died early that

morning. While at the grave the heavy rattle of musketry was distinctly heard to the westward, mingle with the booming of

cannon, which we had noticed an hour before without paying much attention to it, from its being of frequent occurrence.

Hastening back to camp, after the close of the ceremonies, we found the regiment forming for the march.

Our brigade (Jameson's) was ordered forward. Lieutenant Colonel Morgan was in command of the Sixty-third Regiment. We

started out the railroad track, on the usual "route-step"; but had not proceeded far when we were met by a courier from

General Kearney, and the command "double-quick!" was given. Besides arms and accoutrements and sixty rounds of

ammunition in the men's cartridge boxes, we had our canteens and our haversacks filled with three days' rations. We had

had a heavy thunder storm the previous day and night, and although the sky was still clouded, the air was close and sultry.

Sickness had thinned our ranks and considerably weakened most of those still on duty *** For my own part, though not

decidedly sick, I had been rather unfit for nearly two weeks, and when it came to the double quick, I found it very hard to keep

up. Under almost any other circumstances I should have sunk by the wayside; but, by throwing away my haversack and

making extraordinary exertions, I kept my place at the head of the company. Quite a number in the regiment fell out of ranks,

unable to keep it up; but on the regiment pressed toward the awful roar of fire arms, growing closer and louder every moment.

After making two and a half miles on the railroad, we obliqued across some fields to the left and struck the Williamsburg and

Richmond turnpike, near the point known as "Seven Pines." Here we met a stream of men going back - some wounded - but

most flying in panic. We made our way along the turnpike amid a perfect shower of solid shot and shell from the enemy's

batteries, that enfiladed the road and its immediate vicinity. This severe cannonade increased the haste and confusion of the

fugitives, and gave us a foretaste of what was before us.

On we pressed, led and cheered on by General Jameson, who appeared unconscious of danger from the shells bursting on all

sides. We double-quicked over a mile through this rainstorm, meeting now and then a piece of artillery or caisson in full

retreat - having probably run out of ammunition, and fearful of being captured. It was to turn back this tide of battle that we

were pushing forward.

Part of Berry's Brigade of our division had preceded us a little way, and were already engaged in what seemed an unequal

conflict with superior numbers. Casey's Division - the first attacked - had by this time, all fallen far to the rear and were

effectually hors du combat. At length we reached the point where the rifle balls of the enemy began to mingle with their

heavier shot. We halted a moment to allow the left of the regiment to close up. Then up again and forward. For some

distance back there had been woods on both sides; but we had now reached a point where Casey had felled the timber on

both sides, to form an "abattis." Just beyond were the large open fields where his camps had been, and where his deserted

tents were still standing. Here was the enemy's line of battle.

Our regiment was deployed on the left of the road - the One Hundred and Fifth Pennsylvania Volunteers and Eighty-seventh

New York (of our brigade) on the right. We deployed just behind the "slash" or abattis, and had then to march over it, or crawl

through it in line of battle, to reach the front. Just as Company F was filing into line, General Jameson cried out, "Captain Reid,

go in there and don't come out until you have driven every rebel out of that brush!" As soon as the line was formed, we

advanced through the slash, our line resting on the road. This advance was very difficult, owing to the felled and tangled

timber. And all the while bullets and shells were flying like hail, over and among us, coming from an enemy as yet unseen.

A few rods further was a belt of sapling pines and oaks, on the left of the road, not yet felled. Passing a few rods through this

brought us to the front where, just at the edge of the saplings, a slender line of Berry's Brigade was trying to hold its ground

against a host of rebels hid in a strip of brush and fallen timber, close in front of them concealed behind Casey's tents a little

further beyond, and protected by three houses, a long row of cord-wood, and a line of Casey's rifle-pits, still beyond, where

they had captured two of our batteries and were now turning our own guns against us with terrible effect. Here, just in the

edge of the saplings, we halted and opened fire.

The crash and roar was grand. Berry's men were cheered up, and the rebels appalled by the intensity of our steady and rapid

fire. But the firing both ways was intense. Our line was already strewn with dead and wounded. Almost at the first fire,

Sergeant Elgin of my company, a splendid soldier, fell at my side, dead. A little further along the line, to the right, Orderly

Sergeant Delo was a few moments afterward killed. Then Private Rhees fell near the former. Now and then, two, one of my

men would walk or be carried, wounded, to the rear.

We soon discovered that the most deadly fire came from the swampy-brush-wood and fallen timber close by us. We could

see the smoke of the rifles among the brush, and by watching sharply, could distinguish a head or an arm half hidden. It was

evident that the patch of brush was full of rebels, and we soon turned our attention chiefly in that direction. A Michigan man

close by me fell dead, just as he loaded his piece. I thought I saw where the shot came from, and seized his loaded gun in

time to level it at a crouching rebel there, who seemed about to fire again. He was not thirty yards from me. There appeared

to be a race between us; but I shot first, and the rebel rolled over backwards in the swamp, and troubled us no more. Under

the circumstance, I had no compunction about it. I took the balance of the dead man's cartridges and used his gun the rest of

the evening.

That spot soon became too hot for it occupants, and a few tried to fall back from it, but as they had a piece of open field to

pass in order to reach a safer shelter, scarcely one escaped alive. I was there two days afterwards, and although the rebels

had buried great numbers of their dead Saturday night and Sunday, I found that little piece of brushy swamp and abattis

literally filled with rebel dead. The scene was a sad one after the excitement of battle was over.

Middling early in the fight, our Lieutenant Colonel was wounded and carried off the field. Thus left without any field officer, we

fought on, keeping our ground, unsupported by artillery and reinforcements, although the enemy had both. We could plainly

see fresh regiments brought up and deployed in line, strengthening and relieving the others, thinned by our fire. Two or three

times they appeared formed, as for a charge, but they did not attempt it where we were. They did, however, charge on the

extreme right of our brigade and by overwhelming pressure, compelled it to give way.

The enemy followed up their advantage with great vigor and before sundown they had succeeded in flanking us so far on that

side, that they had possession of the turnpike behind us. Then it was that Colonel Campbell coming up with his regiment (the

Fifty-seventh Pennsylvania of our brigade) and our own Colonel Hays with Companies I and K, made such splendid efforts to

turn back the advancing wave. Colonel Hays rapidly gathered up about half a regiment of straggling fugitives, rallied them for

a stand, and forming them about his own companies, led them to the charge, supported by the Fifty-seventh. Both Colonels

and both regiments did gallantly and checked the enemy for awhile, but being reinforced, the latter advanced again with

unbroken front and Colonel Hays' miscellaneous recruits gave way, leaving only Companies I and K to breast the wave. He

reluctantly withdrew from the unequal contest, as did also the Fifty-seventh.

It was sundown and General Jameson had given the order for our whole brigade to fall back to an entrenched position, on the

turnpike about a mile and a half to the rear, having the advantages of wide, open fields in front on both sides of the road,

where our batteries would have a good range to guard against a night attack. Somehow or other, I believe from the

cowardice or other default of our courier charged with the delivery of the order, it never reached us, and after the other

regiments of the brigade had gone safely back, and the enemy had followed them a considerable distance along the turnpike

behind us, we still held our position on the left of the road in the very front of where the hottest of the battle had been.

I knew well, from the direction of the firing on our right, that the enemy had succeeded in flanking us on that side, and there

was still light enough to see fresh regiments beyond the houses moving toward our left. Our men had shot away all their

ammunition, except perhaps one or two cartridges apiece, and had emptied besides, the cartridge boxes of our dead and

wounded. Captain Kirkwood, of Company B, succeeding to the command as senior Captain, asked my advice as to what he

should do. I told him we had done all we could for that day; that under the circumstances, to remain there longer was to

expose what was left of the regiment to be sacrificed or captured as in a few minutes, the only avenue of excape left us

would be cut off. We had sent back all our wounded that we could find; the dead we could not possibly take with us through

the slash and swamps we would have to cross.

Accordingly, the Captain gave the order to fall back slowly, just as it was growing dark. After I had seen that we had left none

of our men behind and could get no further answer to my calls than the whiz of bullets that still came flying from the rifle-pits

behind the house, we turned our men into a by-path that diverged considerably from the main road, which was held by the

enemy in force, and from which they greeted us with random and harmless volleys. A little further on I was struck by a spent

fragment of a shell, causing a slight smart for a few minutes, but without breaking the skin. That was the only time I was even

touched that day by any of the enemy's missiles. I never can be sufficiently thankful to the Almighty God for my preservation

from the showers of bullets that whistled close to me; it seemed almost incredible that I was not touched. I walked through

that belt of little pines on Monday after the battle and it astonished even me to see how almost every sapling of two or three

inches thickness was spotted all over with bullet marks, from the ground up to the height of a man's head. It may be my lot to

be in many another battle, but I do not believe I can ever be placed in a situation of greater apparent danger.

~~~~~

We succeeded in rejoining our brigade at about 10 o'clock that night. We found them on the east side of a large tract of about

a mile square, on both sides of the turnpike, collected and disposed in order of battle---protected in part by earthworks,

commenced by Generals Casey and Couch on their first advance, and which our generals were now busy extending and

strengthening to be ready for emergencies.

Striking across the opening, we found some of Hooker's division which had arrived from the left and rear just as the firing had

ceased. They were fresh for the work in the morning. Inquiring as we went along the lines, we found that Kearney and

Jameson were in the edge of the woods on the north side of the turnpike.

General Jameson was overjoyed to see so many of the Sixty-third safe, and returning in a body in good order. He led us to

Kearney's headquarters, where we found Colonel Hays and the Companies I and K. Here we got some crackers and hot

coffee and rested on our arms until morning. Here, too, we learned that besides Hooker, who came from the left,

Richardson's and Sedgwick's divisions of Sumner's Corps, had arrived from the other side of the Chickahominy on our right,

just in time to give and take, before dark, a volley or two with the left wing of the Rebel Army, which was moving down on the

north side of the railroad, expecting to cut off our retreat. So the prospect for the morning's work was much more agreeable

than it would have been in the absence of such comfortable reinforcements.

Sunday morning the rebels advanced boldly to the attack, coming up to the edge of the woods in front of us, but Hooker's

division on the turnpike and Sumner's troops on the railroad---our brigade being held as a "reserve"---met and routed them in

a couple of hours' fighting, without any need of our help.

Ever since we have been kept in position, changing only by advancing, ready for battle at any moment. There has been some

skirmishing since, between the pickets, and an occasional cannonade from one or both sides, but nothing more as yet. I

think, however, the great Battle of Richmond will be fought this week, if it is to be fought at all.

Our regiment lost twenty-one killed, eighty-one wounded, and seventeen missing.

Source: Gilbert Adams Hays, Captain. Under the Red Patch: Story of the Sixty-third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861

- 1864. Published by the 63d Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment Association. Pittsburgh; Market Review Publishing Company,

1908.

Six and a half miles from Richmond

June 10, 1862

On the memorable 21st of May, our camp was about a mile this side of the Chickahominy, erecting a bridge. Colonel Hays and

Captain Berringer (acting Major) were three or four miles off, southward, inspecting the picket lines of our (Kearney's)

division. At 2 o'clock Company F went to a knoll across the railroad to bury Corporal Dunmire, who had died early that

morning. While at the grave the heavy rattle of musketry was distinctly heard to the westward, mingle with the booming of

cannon, which we had noticed an hour before without paying much attention to it, from its being of frequent occurrence.

Hastening back to camp, after the close of the ceremonies, we found the regiment forming for the march.

Our brigade (Jameson's) was ordered forward. Lieutenant Colonel Morgan was in command of the Sixty-third Regiment. We

started out the railroad track, on the usual "route-step"; but had not proceeded far when we were met by a courier from

General Kearney, and the command "double-quick!" was given. Besides arms and accoutrements and sixty rounds of

ammunition in the men's cartridge boxes, we had our canteens and our haversacks filled with three days' rations. We had

had a heavy thunder storm the previous day and night, and although the sky was still clouded, the air was close and sultry.

Sickness had thinned our ranks and considerably weakened most of those still on duty *** For my own part, though not

decidedly sick, I had been rather unfit for nearly two weeks, and when it came to the double quick, I found it very hard to keep

up. Under almost any other circumstances I should have sunk by the wayside; but, by throwing away my haversack and

making extraordinary exertions, I kept my place at the head of the company. Quite a number in the regiment fell out of ranks,

unable to keep it up; but on the regiment pressed toward the awful roar of fire arms, growing closer and louder every moment.

After making two and a half miles on the railroad, we obliqued across some fields to the left and struck the Williamsburg and

Richmond turnpike, near the point known as "Seven Pines." Here we met a stream of men going back - some wounded - but

most flying in panic. We made our way along the turnpike amid a perfect shower of solid shot and shell from the enemy's

batteries, that enfiladed the road and its immediate vicinity. This severe cannonade increased the haste and confusion of the

fugitives, and gave us a foretaste of what was before us.

On we pressed, led and cheered on by General Jameson, who appeared unconscious of danger from the shells bursting on all

sides. We double-quicked over a mile through this rainstorm, meeting now and then a piece of artillery or caisson in full

retreat - having probably run out of ammunition, and fearful of being captured. It was to turn back this tide of battle that we

were pushing forward.

Part of Berry's Brigade of our division had preceded us a little way, and were already engaged in what seemed an unequal

conflict with superior numbers. Casey's Division - the first attacked - had by this time, all fallen far to the rear and were

effectually hors du combat. At length we reached the point where the rifle balls of the enemy began to mingle with their

heavier shot. We halted a moment to allow the left of the regiment to close up. Then up again and forward. For some

distance back there had been woods on both sides; but we had now reached a point where Casey had felled the timber on

both sides, to form an "abattis." Just beyond were the large open fields where his camps had been, and where his deserted

tents were still standing. Here was the enemy's line of battle.

Our regiment was deployed on the left of the road - the One Hundred and Fifth Pennsylvania Volunteers and Eighty-seventh

New York (of our brigade) on the right. We deployed just behind the "slash" or abattis, and had then to march over it, or crawl

through it in line of battle, to reach the front. Just as Company F was filing into line, General Jameson cried out, "Captain Reid,

go in there and don't come out until you have driven every rebel out of that brush!" As soon as the line was formed, we

advanced through the slash, our line resting on the road. This advance was very difficult, owing to the felled and tangled

timber. And all the while bullets and shells were flying like hail, over and among us, coming from an enemy as yet unseen.

A few rods further was a belt of sapling pines and oaks, on the left of the road, not yet felled. Passing a few rods through this

brought us to the front where, just at the edge of the saplings, a slender line of Berry's Brigade was trying to hold its ground

against a host of rebels hid in a strip of brush and fallen timber, close in front of them concealed behind Casey's tents a little

further beyond, and protected by three houses, a long row of cord-wood, and a line of Casey's rifle-pits, still beyond, where

they had captured two of our batteries and were now turning our own guns against us with terrible effect. Here, just in the

edge of the saplings, we halted and opened fire.

The crash and roar was grand. Berry's men were cheered up, and the rebels appalled by the intensity of our steady and rapid

fire. But the firing both ways was intense. Our line was already strewn with dead and wounded. Almost at the first fire,

Sergeant Elgin of my company, a splendid soldier, fell at my side, dead. A little further along the line, to the right, Orderly

Sergeant Delo was a few moments afterward killed. Then Private Rhees fell near the former. Now and then, two, one of my

men would walk or be carried, wounded, to the rear.

We soon discovered that the most deadly fire came from the swampy-brush-wood and fallen timber close by us. We could

see the smoke of the rifles among the brush, and by watching sharply, could distinguish a head or an arm half hidden. It was

evident that the patch of brush was full of rebels, and we soon turned our attention chiefly in that direction. A Michigan man

close by me fell dead, just as he loaded his piece. I thought I saw where the shot came from, and seized his loaded gun in

time to level it at a crouching rebel there, who seemed about to fire again. He was not thirty yards from me. There appeared

to be a race between us; but I shot first, and the rebel rolled over backwards in the swamp, and troubled us no more. Under

the circumstance, I had no compunction about it. I took the balance of the dead man's cartridges and used his gun the rest of

the evening.

That spot soon became too hot for it occupants, and a few tried to fall back from it, but as they had a piece of open field to

pass in order to reach a safer shelter, scarcely one escaped alive. I was there two days afterwards, and although the rebels

had buried great numbers of their dead Saturday night and Sunday, I found that little piece of brushy swamp and abattis

literally filled with rebel dead. The scene was a sad one after the excitement of battle was over.

Middling early in the fight, our Lieutenant Colonel was wounded and carried off the field. Thus left without any field officer, we

fought on, keeping our ground, unsupported by artillery and reinforcements, although the enemy had both. We could plainly

see fresh regiments brought up and deployed in line, strengthening and relieving the others, thinned by our fire. Two or three

times they appeared formed, as for a charge, but they did not attempt it where we were. They did, however, charge on the

extreme right of our brigade and by overwhelming pressure, compelled it to give way.

The enemy followed up their advantage with great vigor and before sundown they had succeeded in flanking us so far on that

side, that they had possession of the turnpike behind us. Then it was that Colonel Campbell coming up with his regiment (the

Fifty-seventh Pennsylvania of our brigade) and our own Colonel Hays with Companies I and K, made such splendid efforts to

turn back the advancing wave. Colonel Hays rapidly gathered up about half a regiment of straggling fugitives, rallied them for

a stand, and forming them about his own companies, led them to the charge, supported by the Fifty-seventh. Both Colonels

and both regiments did gallantly and checked the enemy for awhile, but being reinforced, the latter advanced again with

unbroken front and Colonel Hays' miscellaneous recruits gave way, leaving only Companies I and K to breast the wave. He

reluctantly withdrew from the unequal contest, as did also the Fifty-seventh.

It was sundown and General Jameson had given the order for our whole brigade to fall back to an entrenched position, on the

turnpike about a mile and a half to the rear, having the advantages of wide, open fields in front on both sides of the road,

where our batteries would have a good range to guard against a night attack. Somehow or other, I believe from the

cowardice or other default of our courier charged with the delivery of the order, it never reached us, and after the other

regiments of the brigade had gone safely back, and the enemy had followed them a considerable distance along the turnpike

behind us, we still held our position on the left of the road in the very front of where the hottest of the battle had been.

I knew well, from the direction of the firing on our right, that the enemy had succeeded in flanking us on that side, and there

was still light enough to see fresh regiments beyond the houses moving toward our left. Our men had shot away all their

ammunition, except perhaps one or two cartridges apiece, and had emptied besides, the cartridge boxes of our dead and

wounded. Captain Kirkwood, of Company B, succeeding to the command as senior Captain, asked my advice as to what he

should do. I told him we had done all we could for that day; that under the circumstances, to remain there longer was to

expose what was left of the regiment to be sacrificed or captured as in a few minutes, the only avenue of excape left us

would be cut off. We had sent back all our wounded that we could find; the dead we could not possibly take with us through

the slash and swamps we would have to cross.

Accordingly, the Captain gave the order to fall back slowly, just as it was growing dark. After I had seen that we had left none

of our men behind and could get no further answer to my calls than the whiz of bullets that still came flying from the rifle-pits

behind the house, we turned our men into a by-path that diverged considerably from the main road, which was held by the

enemy in force, and from which they greeted us with random and harmless volleys. A little further on I was struck by a spent

fragment of a shell, causing a slight smart for a few minutes, but without breaking the skin. That was the only time I was even

touched that day by any of the enemy's missiles. I never can be sufficiently thankful to the Almighty God for my preservation

from the showers of bullets that whistled close to me; it seemed almost incredible that I was not touched. I walked through

that belt of little pines on Monday after the battle and it astonished even me to see how almost every sapling of two or three

inches thickness was spotted all over with bullet marks, from the ground up to the height of a man's head. It may be my lot to

be in many another battle, but I do not believe I can ever be placed in a situation of greater apparent danger.

~~~~~

We succeeded in rejoining our brigade at about 10 o'clock that night. We found them on the east side of a large tract of about

a mile square, on both sides of the turnpike, collected and disposed in order of battle---protected in part by earthworks,

commenced by Generals Casey and Couch on their first advance, and which our generals were now busy extending and

strengthening to be ready for emergencies.

Striking across the opening, we found some of Hooker's division which had arrived from the left and rear just as the firing had

ceased. They were fresh for the work in the morning. Inquiring as we went along the lines, we found that Kearney and

Jameson were in the edge of the woods on the north side of the turnpike.

General Jameson was overjoyed to see so many of the Sixty-third safe, and returning in a body in good order. He led us to

Kearney's headquarters, where we found Colonel Hays and the Companies I and K. Here we got some crackers and hot

coffee and rested on our arms until morning. Here, too, we learned that besides Hooker, who came from the left,

Richardson's and Sedgwick's divisions of Sumner's Corps, had arrived from the other side of the Chickahominy on our right,

just in time to give and take, before dark, a volley or two with the left wing of the Rebel Army, which was moving down on the

north side of the railroad, expecting to cut off our retreat. So the prospect for the morning's work was much more agreeable

than it would have been in the absence of such comfortable reinforcements.

Sunday morning the rebels advanced boldly to the attack, coming up to the edge of the woods in front of us, but Hooker's

division on the turnpike and Sumner's troops on the railroad---our brigade being held as a "reserve"---met and routed them in

a couple of hours' fighting, without any need of our help.

Ever since we have been kept in position, changing only by advancing, ready for battle at any moment. There has been some

skirmishing since, between the pickets, and an occasional cannonade from one or both sides, but nothing more as yet. I

think, however, the great Battle of Richmond will be fought this week, if it is to be fought at all.

Our regiment lost twenty-one killed, eighty-one wounded, and seventeen missing.

Source: Gilbert Adams Hays, Captain. Under the Red Patch: Story of the Sixty-third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861

- 1864. Published by the 63d Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment Association. Pittsburgh; Market Review Publishing Company,

1908.

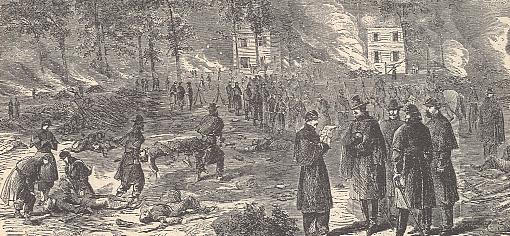

| Illustration from the book, "The Civil War in Pictures: from the Drawing Boards of the Newspaper Artists who Recorded the Conflict," published in 1955. The caption reads, "The Army of the Potomac burying the dead at Fair Oaks Station, VA." |

| Letters, Diaries and Newspaper Articles: Battle of Seven Pines/Fair Oaks |

Oliver Wendell Holmes, newspaper reporter

"May 31st

We heard heavy firing from Casey's Division and soon our Division was under arms and marched four miles, I should think,

the last part through a stream above our knees and then double-quick through mud a foot deep on the field of battle. Soon we

filed round and formed under fire in second position, left of a New York Regiment and opened fire on the Reb line which was

visible. Our fire was soon stopped and we could see in the field Rebs moving by twos and threes, apparently broken up.

When we got to the road, the right wing entered the woods firing hard and the left wing advancing more slowly to avoid

getting fired into by our own men. A company of Rebs trying to pass out of the woods was knocked to pieces and thus we

took the final position of the first day. Here we blazed away left oblique into the woods, till we were ordered to cease firing

and remained masters of the field. We licked them and this time there was the maneurvering of a battle to be seen, splendid

and awful to behold. It is singular what indifference one gets to look on the dead bodies in gray clothes, which lie all around.

As you go through the woods you stumble, perhaps tread on the swollen bodies, already fly blown and decaying, of men shot

in the head, back or bowels. Many of the wounds are terrible to look at."

"May 31st

We heard heavy firing from Casey's Division and soon our Division was under arms and marched four miles, I should think,

the last part through a stream above our knees and then double-quick through mud a foot deep on the field of battle. Soon we

filed round and formed under fire in second position, left of a New York Regiment and opened fire on the Reb line which was

visible. Our fire was soon stopped and we could see in the field Rebs moving by twos and threes, apparently broken up.

When we got to the road, the right wing entered the woods firing hard and the left wing advancing more slowly to avoid

getting fired into by our own men. A company of Rebs trying to pass out of the woods was knocked to pieces and thus we

took the final position of the first day. Here we blazed away left oblique into the woods, till we were ordered to cease firing

and remained masters of the field. We licked them and this time there was the maneurvering of a battle to be seen, splendid

and awful to behold. It is singular what indifference one gets to look on the dead bodies in gray clothes, which lie all around.

As you go through the woods you stumble, perhaps tread on the swollen bodies, already fly blown and decaying, of men shot

in the head, back or bowels. Many of the wounds are terrible to look at."

Henry Abbott, 20th Massachusetts

"In about an hour we let up on the firing along the line, the smoke partially cleared and we saw the rebels charging from the

woods to take Rickets' battery, which, by the way, did admirably. Instantly there went up a tremendous shout along the line

and the biggest volley of the battle sent the rebels yelping into the woods. Then our whole line charged, the first half the

distance in quick time, without cheering, except from old Sumner, who cheered us as we passed, the second half the way

taking the double-quick with the loudest cheers we could get up. It was now dark. We lay on our arms, on marshy ground,

without blankets, officers being obliged to sit up, everybody wet through as to his feet and trousers, and we had brought our

blankets, but gave them all up to the wounded prisoners, of whom our regiment took a large number. My company took ten

unwounded and eleven wounded rebels prisoner in the woods. Among the former, five of the celebrated Hampton Legion of

South Carolina and one Tennessee, two North Carolinians, a Georgia and a Louisiana Tiger. Among the wounded, Brig. Gen.

Pettigrew of South Carolina and Lt. Col. Bull of the 35th Georgians. Pettigrew had given up all his side arms to some of his

people before they ran away, in anticipation of being taken prisoner, and had only his watch, which of course, I returned to

him. Pettigrew will get well. Bull had his side arms, of which I allowed Corporal Summerhayes, his captor, to keep his

pistol, an ordinary affair, while I kept his sword, an ordinary US infantry sword, which I intended to send as a present to you,

but the Colonel knowing his family address, wants me to send it to them and as the poor fellow is dead, of course, I can't

hesitate to do anything which would comfort his family. His scabbard, however, I found very convenient, as mine got broken

in the battle and I threw it away. I am going to send you, instead, a short rifle which I took from a Hampton's Legion fellow,

who were all around with them and the sword bayonet. The rest of the rifles we, of course, turned over to the Colonel, as in

duty bound, except one revolving Colt's rifle, five barrels, worth $60 or $70 apiece which one of my men took from a dying

officer and which I let him keep as a reward of valor."

"In about an hour we let up on the firing along the line, the smoke partially cleared and we saw the rebels charging from the

woods to take Rickets' battery, which, by the way, did admirably. Instantly there went up a tremendous shout along the line

and the biggest volley of the battle sent the rebels yelping into the woods. Then our whole line charged, the first half the

distance in quick time, without cheering, except from old Sumner, who cheered us as we passed, the second half the way

taking the double-quick with the loudest cheers we could get up. It was now dark. We lay on our arms, on marshy ground,

without blankets, officers being obliged to sit up, everybody wet through as to his feet and trousers, and we had brought our

blankets, but gave them all up to the wounded prisoners, of whom our regiment took a large number. My company took ten

unwounded and eleven wounded rebels prisoner in the woods. Among the former, five of the celebrated Hampton Legion of

South Carolina and one Tennessee, two North Carolinians, a Georgia and a Louisiana Tiger. Among the wounded, Brig. Gen.

Pettigrew of South Carolina and Lt. Col. Bull of the 35th Georgians. Pettigrew had given up all his side arms to some of his

people before they ran away, in anticipation of being taken prisoner, and had only his watch, which of course, I returned to

him. Pettigrew will get well. Bull had his side arms, of which I allowed Corporal Summerhayes, his captor, to keep his

pistol, an ordinary affair, while I kept his sword, an ordinary US infantry sword, which I intended to send as a present to you,

but the Colonel knowing his family address, wants me to send it to them and as the poor fellow is dead, of course, I can't

hesitate to do anything which would comfort his family. His scabbard, however, I found very convenient, as mine got broken

in the battle and I threw it away. I am going to send you, instead, a short rifle which I took from a Hampton's Legion fellow,

who were all around with them and the sword bayonet. The rest of the rifles we, of course, turned over to the Colonel, as in

duty bound, except one revolving Colt's rifle, five barrels, worth $60 or $70 apiece which one of my men took from a dying

officer and which I let him keep as a reward of valor."

Samuel Aven Smith

With many thanks to Samuel E. Smith for sharing an excerpt from the journal of his g-grandfather,

who lost a leg in the Battle of Seven Pines, and went on to become a doctor in York County, South

Carolina.

March, 1862. The army evacuated Centerville and fell back to Richmond, the capital of the Confederate States. After

reorganizing for the war, a large portion of the army was sent to York-Town to meet and check the Northern Army. Then

commanded by Gen. McClellen. He had a grnd and well-equipped and disciplined [army]. General Joseph E. Johnson was

then in command of The Southern forces at that point. Under the new organization, I joined Company F 5th SC Regt, then

commanded by Captain Fitchet. The company was known by the name of the Kings Mountain Guards.

I gave my last bite of bread to David Harrison, a soldier from my native county. He looked so pitiful that I could not resist

giving him my last bread. The next day I bought half pint of peas which I boiled in a tin cup with neither meat or salt to season

my peas but they relished well to a hungry stomach.

While on this march I was nearly necked. My clothing was worn out but when we arrived at Richmond I received a new suit

from my Mother which made me feel proud. A kind mother never forgets her son. May 31st, I put on my new suit. The Longe

Roll beat; and every [man] ordered to be in line without delay. The battle of Seven Pines had began its bloody wash. As we

marched to the battlefield my mind was sad and gloomy. Though I had no fear about me, yet did not feel that all was right.

After we had fought for two or three hours, I was wounded through both legs. My left leg was much worse than the right leg.

On June 28th, 1862 my left leg was amputated four inches below the knee joint, my foot leg having mortified. There was no

other alternative for life except to take it off. My leg was amputated by my own request and was glad to get rid of it; but still

my leg did not do well, being so exhausted, Gangreen took hold of my wound and assumed a malignant form which was the

most intense suffering that a human could endure. Death itself would be pleasant and even preferred to that of Gangreen. A

human being living and looking at his own flesh decaying and falling off is indescribable, to say nothing of his agony. August

14th, I arrived at home and by the help of God, I began slowly to recuperate.

My Mother was my nurse and the Rev. W. W. Carothers visited me frequently to see after my soul's interest.

I went to the Medical College of South Carolina in 1865. When attending the Course of Lectures in the City of Charleston, I

applied myself closely and made a good stand on examinations. Dr. Harvy Witherspoon of Yorkville was in college with me.

He was an excellent man; had high-toned principles.

When I left Colloege I had barely enough change to pay expenses home.

With many thanks to Samuel E. Smith for sharing an excerpt from the journal of his g-grandfather,

who lost a leg in the Battle of Seven Pines, and went on to become a doctor in York County, South

Carolina.

March, 1862. The army evacuated Centerville and fell back to Richmond, the capital of the Confederate States. After

reorganizing for the war, a large portion of the army was sent to York-Town to meet and check the Northern Army. Then

commanded by Gen. McClellen. He had a grnd and well-equipped and disciplined [army]. General Joseph E. Johnson was

then in command of The Southern forces at that point. Under the new organization, I joined Company F 5th SC Regt, then

commanded by Captain Fitchet. The company was known by the name of the Kings Mountain Guards.

I gave my last bite of bread to David Harrison, a soldier from my native county. He looked so pitiful that I could not resist

giving him my last bread. The next day I bought half pint of peas which I boiled in a tin cup with neither meat or salt to season

my peas but they relished well to a hungry stomach.

While on this march I was nearly necked. My clothing was worn out but when we arrived at Richmond I received a new suit

from my Mother which made me feel proud. A kind mother never forgets her son. May 31st, I put on my new suit. The Longe

Roll beat; and every [man] ordered to be in line without delay. The battle of Seven Pines had began its bloody wash. As we

marched to the battlefield my mind was sad and gloomy. Though I had no fear about me, yet did not feel that all was right.

After we had fought for two or three hours, I was wounded through both legs. My left leg was much worse than the right leg.

On June 28th, 1862 my left leg was amputated four inches below the knee joint, my foot leg having mortified. There was no

other alternative for life except to take it off. My leg was amputated by my own request and was glad to get rid of it; but still

my leg did not do well, being so exhausted, Gangreen took hold of my wound and assumed a malignant form which was the

most intense suffering that a human could endure. Death itself would be pleasant and even preferred to that of Gangreen. A

human being living and looking at his own flesh decaying and falling off is indescribable, to say nothing of his agony. August

14th, I arrived at home and by the help of God, I began slowly to recuperate.

My Mother was my nurse and the Rev. W. W. Carothers visited me frequently to see after my soul's interest.

I went to the Medical College of South Carolina in 1865. When attending the Course of Lectures in the City of Charleston, I

applied myself closely and made a good stand on examinations. Dr. Harvy Witherspoon of Yorkville was in college with me.

He was an excellent man; had high-toned principles.

When I left Colloege I had barely enough change to pay expenses home.

Nicholas Ford, 67th Infantry Regiment, New York

With much appreciation to Jack Ford, who has shared a letter that his g-g-grandfather, Pvt. Nicholas Ford, wrote to his wife,

Mary, in October, 1861. Nicholas Ford was killed at the Battle of Seven Pines/Fair Oaks.

To see an image of the letter, click here.

I left the images large, so they could be easily read; if you are on dial-up, you might prefer to pull up the pages one at a time:

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Envelope

With much appreciation to Jack Ford, who has shared a letter that his g-g-grandfather, Pvt. Nicholas Ford, wrote to his wife,

Mary, in October, 1861. Nicholas Ford was killed at the Battle of Seven Pines/Fair Oaks.

To see an image of the letter, click here.

I left the images large, so they could be easily read; if you are on dial-up, you might prefer to pull up the pages one at a time:

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Envelope

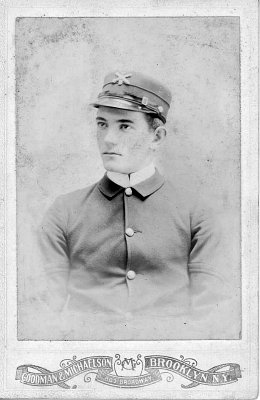

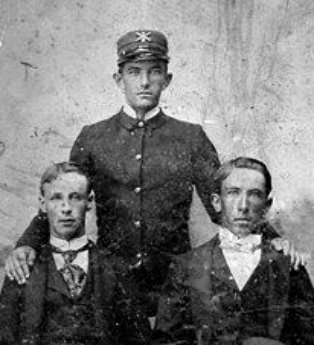

| Above, Nicholas Ford, standing; with his brothers, William S. and Andrew J. Ford, who, also, enlisted in the Union Army. At the time of their enlistment, Andrew was 21 and William was 18. Right, Nicholas Ford, who wrote the letters below. Many thanks to Valerie Posillico for sharing these photos. Nicholas Ford was her 3-g-uncle. |